The rise of Exhange Traded Funds ('ETFs') is now becoming interesting and has really energised the whole 'active-passive' debate in the last 2 years. Pioneered in the UK by Barclays (IShares) there has been an increasing number of new entrants into the UK market, which are far more dynamic in both product and marketing than the 'trackers' of old.. Once there was not much challenge for active fund managers since trackers were pretty uncompetitive and agricultural beasts, offering exposure to a handful of markets..and really for the

pie n chips TESSA/PEP/ISA and pension brigade.. UK FTSE100 or Global Equity were typical..

Now companies such as Vanguard, IShares and Dimensional are keeping active managers on their toes.

Current largest ETF providers in the International (non-US) market: Source Ronin Research

Active managers have been under fire for many years in proving and justifying their

alpha and management charges. Back in 2006 I remember Garbriel Burstein of Reuters fame presenting about 'alpha as the factor of betas'.. what he meant was that very little 'alpha' could actually be found on investigation - indeed many of the founders of CAPm and MPT (Capital Asset Pricing model and Modern Portflio Theory) refined the original crude calculations to account for this (the basic formula are still the ones used in fact sheets today). In reality many active managers just bought more risk or got lucky on the timing.. some were in fact passive in tracking an index but still charging for an active approach.. naughty naughty! Back then I opposed such a view but in 10 years of fund analysis it's true that I have found little

alpha that I could confidently attribute back to a fund manager.

There are 2 distinct polarised sides to this debate - Active managers who charge an investment fee to beat the market and the 'Passive' managers who charge less to provide the returns of the market. However the situation has become increasingly muddied by the introduction of Active-Passive funds from the likes of 7iM (Seven Investment Mgt) and IShares (Blackrock) adds another dimension and more difficult options for the investor. These are Fund of Funds ('FoFs') where the manager invests in low cost ETFs instead of actively managed funds.. nifty! It's fair to say that they offer multi-manager funds (and FoFs) a lifeline as they have been long-derided for their 'double tap' charging..

So - on one hand active managers will point towards the creation of 'alpha'.. that is the residual return over markets, and revel in the fact that indices do have a habit of levelling out over the longer-term (leaving ISA investors with 0% after 3-5 years). On the other side ETF and passive fund providers point out that few active manager funds can actually generate 'alpha' consistently and over-charged for the priviledge.

2 things are largely unknown in the UK today - 1) does active or passive return the best returns - there is so much propaganda on both sides that investors have little chance of knowing; nor is active and passive performance adequately benchmarked to allow investors make a fair decision. 2) when do active and passive strategies perform (for the same reason) and thus which offers the best bang for your buck.

In my experience passive funds tend to do well in the early-mid-phase of a recovery and thus low drag is key; when it's hard to beat the index. Active managers take the advantage in the mid-late phase as the market becomes more frothy and outright index returns less prominent (2nd phase).

In favour of Passive funds: (not neccessarily old style 'trackers')

- 'WYSIWYG' - i.e. transparency = if the FTSE100 moves up 10% - so does your ETF (some active sectors allow for a broad array of approaches than can mislead the investor; others are opaque in nature and difficult to understand)

- Low cost - often it's easy to trade ETFs with flat fees - generally an investor can enjoy a much lower )or zero) annual fee (reduction in yield, 'RiY'). The TER of most active funds will be around 1.5-2.5% p.a. The charging structure of ETFs suits investors who like to keep any investment advice distinct from their investment allocation

- Past performance is, relatively speaking, easier to attribute to an ETF than an active fund

- Mobility - it's easier and cheaper to move in and out of ETFs through online trading (active maangers rely on reoccuring fee structures - it is not in their interests to have short-term assets and as such they often penalize those who try to withdraw their money within 6-18mo of investing.. some might say this is not 'TCF' friendly; albeit perfectly 'legal' in the current market

- No people risk - there is no risk of errors, no threat of a loss of a key manager etc, generally speaking there are no good or bad ETFs (lenders perhaps) so choice between ETFs in the same sector comes down mostly to ease of access and price

- Liquidity - ETFs appear to be easy to trade with a deep market to SELL when you want, usually same day; (active managers can delay in selling out and returning your assets). This also tends to minimize FX risk

- An ETF is individually unaffected by the inflows/outflows of the fund manager or how big/deep the market becomes (some fund managers can become hamstrung when trying to handle large sums; some mandates need large sums to have buying power and struggle if they lose assets - victims of their own success/failure)

- There is no need to benchmark an ETF (relative return is a sin of the active management industry imo - benchmarks are often chosen on ability to be beaten and often deviate substantially from the fund; composites on the other hand lack real-world or transparency for the investor

- All past performance can be attributed back to the ETF/index without need to check for changes in people, process or portfolio - comers back to WYSIWYG

- Diversification - you can buy one ETF to cover 500, 5000, 25,000 stocks... they are also easier to allocate into a larger portfolio with less chance for overlap or unwanted concentration (fund managers are known to drift, rotate which makes tracking your active exposure very tricky - most only report their top 10 holdings on a monthly basis)

- Investor control - the ability to tactically manage your own targets and take you rown view on markets

- Generally speaking ETFs suit those investors whom want to invest for the short-medium term

In favour of Active funds: (open-ended; closed funds such as Investment Trusts are different)

- Clarity of process and position against the market - a 'people' element

- The promise of diversification and stock selection to minimize downside

- In some cases a higher beta strategy (like a growth fund) will be expected to outperform in a rising market by buying smaller companies or weighting in favour of more cyclical sectors (E.g. Technology)

- Income managers can use cash flow to diversify the risk of price volatility - known as a total return strategy

- Active managers can plan when to BUY and SELL - to time the market and take advantage of price drops, avoid price bubbles, herding or capitalise on over-liquidity in certain sectors

- Through superior analysis active managers can potentially spot inefficiencies in the market such as a stock price and take advantage

- Some active managed funds are designed to suit a certain attitude to risk or investment horizon (risk based and target maturity funds) - this allows the investor to largely fire n forget their investment until such time they want to encash or change, useful for those who prefer to avoid financial advice

- Most actve managers can hold alternate assets for limited times or rotate to cash in the event of a downturn - some managers have perfected this to become 'all weather' managers

- Most active managers can now hedge their long-positions (it's less easy to hedge efficiently through ETFs) and they can also hedge their FX exposure when investing overseas

- Some strategies such as Absolute Return are difficult to index and thus recreate as an ETF, they are designed to be less cyclical and (all other things being equal) then past performance could be a better indicator for that type of strategy than for a 'blind' index product (this is FSA blastphemy I know!!)

- There remains more choice of strategy among active managers than in passive funds; (the gap is narrowing)

- Many active funds offer different share classes to suit investor needs; some offer currency protection when enchashing units in a fund denominated in a different currency

- More modern boutiques are beginning to offer performance-related fee structures

- Increasing use of single NAV pricing (OEICS, SICAVs) means there is usually no bid-offer spread to worry about at encashment

- Generally speaking active funds suit those investors whom want to invest for the medium-long term

So the first point to make here is that neither can be a 'single solution' no matter what the providers or advisers tell you - active will suit some; passive others.

Passive funds often do better on the downside than active; (unless the manager is particuarly good at being defensive) due to lower Reduction in Yield (the 'RiY'). This comes down to simple costs v returns. Most active managers will continue to charge even when returns in their Fund are falling! The resulting cancellation of units then not only increases losses but it also comprimises the subsequent recovery. Key here is the implications on mainstream active fund managers applying performance-linked fees.. In the UK there is a skewed perception we have of index products such as ETFs being only equity-based. In fact there is a broad range of asset classes available.. given the large asset rotations it's plausible that passive strategies are an easier way to manage your asset allocation against herding and sentiment risks.. Europe and the US have already taken advantage and the UK will be next.

Passive charges = [Flat trading charge on entry (usually <1%), flat charge on exit (usually <1%), typically no annual charge, price Bid/Offer spread (market quoted, typically 2-5%) on sale.]

Active charges = [Initial charge (can be up to 6%), total annual charge which can include: management fee, admin fee, custodial fee, distirbution fee (typically 1.5-2% p.a.), price Bid/Offer spread (typically 5%) on sale unless mid-point priced, early redemption fee (can be up to 5%) on some funds in the first 1-3 years.]

Outcome = As a rough estimate of the above then any given ETF may cost the investor 7% (usually much less) in fees over a 3 year period; compared to anywhere between 9.5%-17% over the same period for an active fund. IF assuming reinvestment over those 3 years, similar underlying assets and a growing market, then the impact annual charges would have on a compounding return would make that difference even greater (c.2.5%-10%)!! This places a great amout of onus on the active maanger to at least find a residual for the same level of risk, over the ETF, or return even more gains, proportionally to the risk taken (hence more skill).

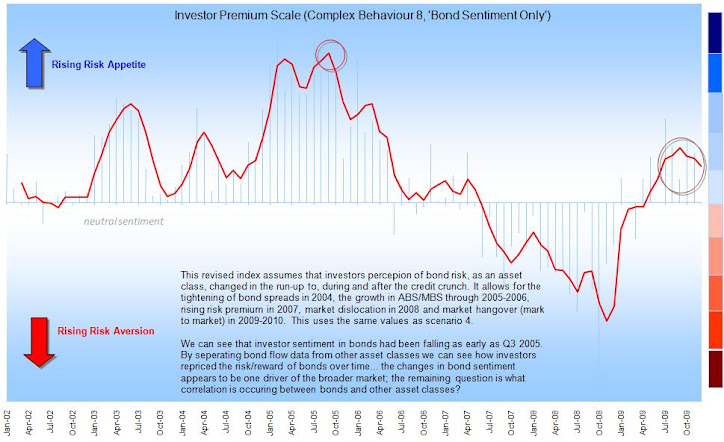

What my analysis showed is that an investor could manage a passive portfolio tactically to take advantage of large herding patterns. This involves risk, access to the right data, practice and above all discipline. What then for the rise of active-passive funds? Such funds will rely heavily on asset-allocation and avoiding unneccessary churning of their positions to keep trading costs down. Again this comes down to what premium is being charged for this investment 'skill', how easy such composites will be to benchmark and whether returns prove that active-passive is more than a neat re-packaging trick. For more info please feel free to refer to my CCC 'ETF' guide below the blog. I will re-jig it in the next cpl of weeks to make it a better read; (I'll be the first to admit it's a bit muddled.. stay tuned!). You could also consider building up your own logic grid to compare an active versus passive fund (see how by reading my guide on 'Choosing Mutual Funds - ')..

I suspect Active-Passive funds will take some benefits from both sides but I doubt they will offer the best of both..

Active management is all about trust - the money remains yours; you entrust it to an 'expert' to invest better than you can. If they consistently can do no better than what is available to you already, and for less, then you are simply paying a premium for a placebo.. a peace of mind which may or may not be misplaced. In truth I suspect this is exactly what a large % of the UK retail market is being encouraged to do.. it is the fear that has helped the retail pooled investment industry grow for many years.

+Nov09.bmp)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.